Indigenous knowledge and artificial intelligence are helping protect baby turtles from predators on Cape York. A partnership between CSIRO, Aak Puul Ngantam Cape York and Microsoft has given Indigenous rangers a helping hand in analysing tens of thousands of images of Cape York coastline. What used to take one month of difficult on-ground work can now be achieved in hours. This is increasing the chances of survival for these threatened and culturally important species.

Hub research has built upon existing partnerships between Indigenous rangers and CSIRO researchers by utilising artificial intelligence (AI) and cloud computing to automatically analyse tens of thousands of aerial images. Previously, this analysis had been done through a lengthy ‘send and receive’ process between researchers and rangers. With the help of Microsoft AI, this feedback loop is shrinking so that rangers get the information they need in almost real-time.

Sea turtle hatchlings already face a dangerous journey from nest to ocean, and feral pigs on Cape York make these journeys even more hazardous – the pigs dig up freshly laid turtle nests and can eat every egg in a nest. Three types of turtles nest on Cape York beaches: Hawksbills, Olive Ridleys and Flatback turtles. Olive Ridleys are the biggest concern. Their nests are shallow and are generally laid on the beach rather than in the dune. This leaves the nest vulnerable to predators, particularly pigs.

Large wet seasons can inundate the landscape and make large sections of coastline inaccessible to rangers. Photo: APN Cape York archive.

Project leader, CSIRO’s Dr Justin Perry, has been working with rangers from Aak Puul Ngantam (APN) Cape York for the last 10 years and recently, they’ve turned their attention to protecting turtles from feral pig predation. The project team worked together for eight years before beginning to consider technical solutions.

It was important to Traditional Owners and APN Cape York rangers to protect turtles. APN Cape York ranger Dion Koomeeta emphasised the importance of using Indigenous knowledge and science to protect baby turtles.

We use science to protect the turtles so our next generation can know what the turtles look like. It’s a good thing for the kids to learn the ranger stuff so when they grow up they can protect the land for the next generation to come. Most of the pigs are destroying our beaches. Normally they go round digging up all the nests. By the time we get down there, there’s not many eggs in a nest.

– Mr Dion Koomeeta, APN Cape York ranger

APN ranger Dion Koomeeta values working on the ground to share knowledge about turtles with future generations. Photo: Phisch Creative – Phil Schouteten.

Kerri Woodcock from Cape York Natural Resource Management coordinates the Western Cape Turtle Threat Abatement Alliance. The alliance works with Indigenous ranger groups all across Cape York to help protect baby turtles.

The most important immediate threat to turtle populations on the western Cape is predation of their nests by feral pigs. The pigs dig up their nests and eat the turtle eggs. Without intervention, there can be zero survival of the baby turtles.

– Ms Kerri Woodcock, Cape York Natural Resource Management

Protecting turtles on Cape York has the added complication of dealing with monsoonal weather and the complications this weather brings – waist-deep and boggy floodplains that are often frequented by crocodiles, and impassable roads or tracks that prevent beach access.

Control methods have previously been able to reduce feral pig predation of nests by up to 90%, but monitoring the effectiveness of management actions is hampered by accessibility, distance, and road and weather conditions.

APN rangers have become skilled drone pilots to overcome some of the accessibility challenges of moving around Cape York during the wet season. Photo: Phisch Creative – Phil Schouteten.

Turtles begin nesting in June, but rangers often can’t get to the nesting beaches until later in July or August, particularly after big wet seasons.

Aerial images from helicopters have been collected in the past, but required hours of detailed scrutiny to provide any useful information.

The feedback – very clear feedback – from the rangers was, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if we could get this [nest and pig track information] in real-time so we can make decisions on the beach?’

– Dr Justin Perry, Project Leader, CSIRO

Steve van Bodegraven, a machine learning engineer with Microsoft, explains that simply uploading the photos from a drone or helicopter-mounted camera begins the analysis process with this new approach.

When the rangers get back in from the land and back onto Wi-Fi with their surveys, the images are uploaded to the cloud, where they’re automatically analysed. The models sort the landscape photos and find turtle nests, turtle tracks and pig tracks, which are surfaced in a dashboard.

– Mr Steve van Bodegraven, Machine Learning Engineer, Microsoft

Helicopters and drones are used for aerial photo surveys that monitor turtle nests and predators. Photo: APN Cape York archive.

Lee Hickin, Microsoft Australia’s chief technology officer, emphasised that the more images it analyses, the better the AI becomes at identifying the different tracks and indicators in different contexts – machine learning at its best.

Together the teams are using machine learning to train and refine the models.

– Lee Hickin, Chief Technology Officer, Microsoft Australia

Using cloud computing and AI is accelerating the process of identifying the sections of coastline that will benefit most from management actions. Putting this information at rangers’ fingertips allows them to make much faster and more efficient interventions to protect turtle nests and baby turtles.

We can now monitor twice the length of the coastline in two hours instead of a month. The more we can automate that monitoring process, the more the rangers can focus on actual management work. Monitoring exists to inform adaptive management. That’s the actual critical step in closing the adaptive management loop – not just having the information – but having it when you need it.

– Dr Justin Perry

The project is just one example of how the Australian Government is tackling our big environmental challenges with scientific research that delivers practical tools to support effective, real-time, on-ground actions.

– The Hon Sussan Ley, Former Minister for the Environment

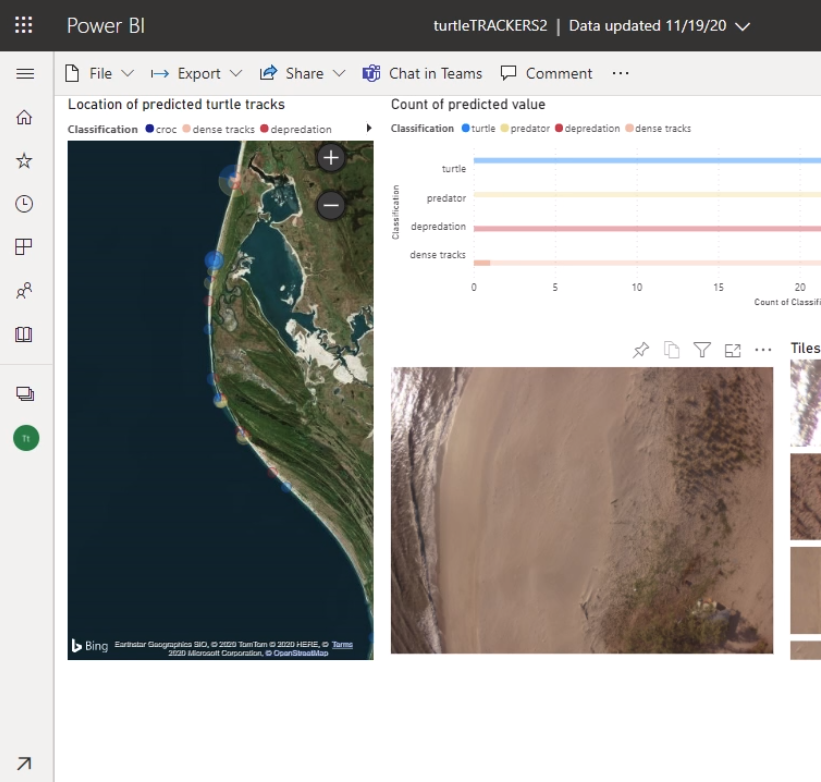

The insights from the AI analysis are then shared with rangers using a Power BI (business intelligence) dashboard, which displays the classified tracks, predation incidents and nests in formats that are immediately useful to the rangers.

The Power BI dashboard displays insights from drone and helicopter photos that can help rangers make decisions about where to target their management actions.

Incorporating AI is providing a huge benefit to rangers working on the ground, but continued collaboration between all stakeholders is needed for a long-term solution to the threats faced by baby turtles.

This research showcases how the National Environmental Science Program is forging partnerships that bring together Indigenous knowledge and western science to achieve a better environmental and community outcome.

– The Hon Sussan Ley, Minister for the Environment

It’s going to take all of us to solve this problem – Indigenous rangers, science and technology all have a role to play. But working with CSIRO and Microsoft is a perfect example of how we can use science and technology to achieve positive management outcomes on-ground.

– Ms Kerri Woodcock

This project also highlights the value of strong collaborative partnerships, not only for applied management solutions on the ground, but for sharing these lessons and methods more broadly.

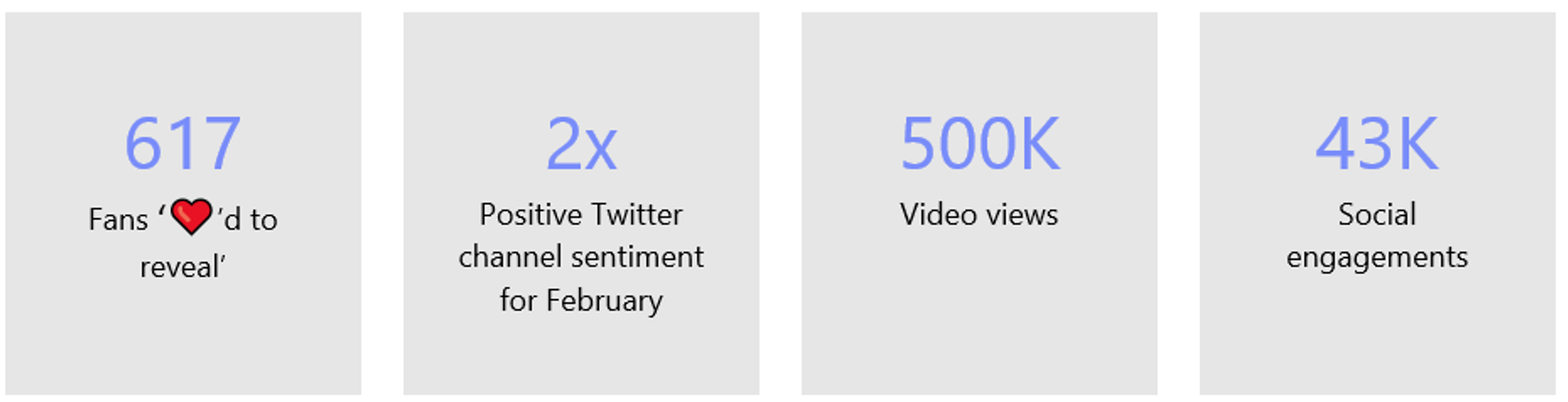

The success of partnering with Microsoft’s AI for Earth program meant that Microsoft lent its full weight to sharing the stories of the environmental benefits of this research. Microsoft’s creative and communications teams – in Australia and North America – amplified these success stories through a campaign that multiplied many times the communications capacity that was already involved in the project through the Hub, CSIRO and APN Cape York. Brad Smith, President of Microsoft, even shared the story on LinkedIn. Microsoft’s social media campaign has been shortlisted for a Mumbrella CommsCon Award for Best Use of Owned Media.

Interim statistics from Microsoft’s social media campaign indicate wide social engagement with the video and post.

The fruits of this research are also being disseminated globally. Although this technology and approach were developed specifically for Cape York, the analysis code is available for anyone to download and could help protect turtles and their nesting sites all around the world.

Research outputs

Scientific papers

Media (selection)

Factsheets

Videos

Impact stories

Project webpage

Attributions

We acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples as the traditional custodians of the lands on which we work. We pay our respects to Elders of the past and present, and acknowledge their spiritual connection to Country. In particular we would like to acknowledge the Wik and Kugu people of the region where this project took place.