Our analysis showed that the revised, optimal design of the monitoring program meant that fewer sites needed to be surveyed in Kakadu, if adequate sites were also surveyed in nearby protected areas with similar habitats, such as national parks and Indigenous Protected Areas. However, sites needed to be surveyed more intensely and frequently to better detect trends. The optimised design saw the number of sites surveyed in Kakadu reduced from 125 to 50, with sites surveyed every 3 years instead of every 5 years. The revised methods included an extra night of live trapping for mammals and reptiles, an increased number of pitfall traps and funnel traps, additional time spent searching for birds and reptiles, and the introduction of motion-sensing camera traps. Automated camera traps can greatly improve the detection of many species. Five camera traps were deployed at each site with 3 different setups to target different fauna.

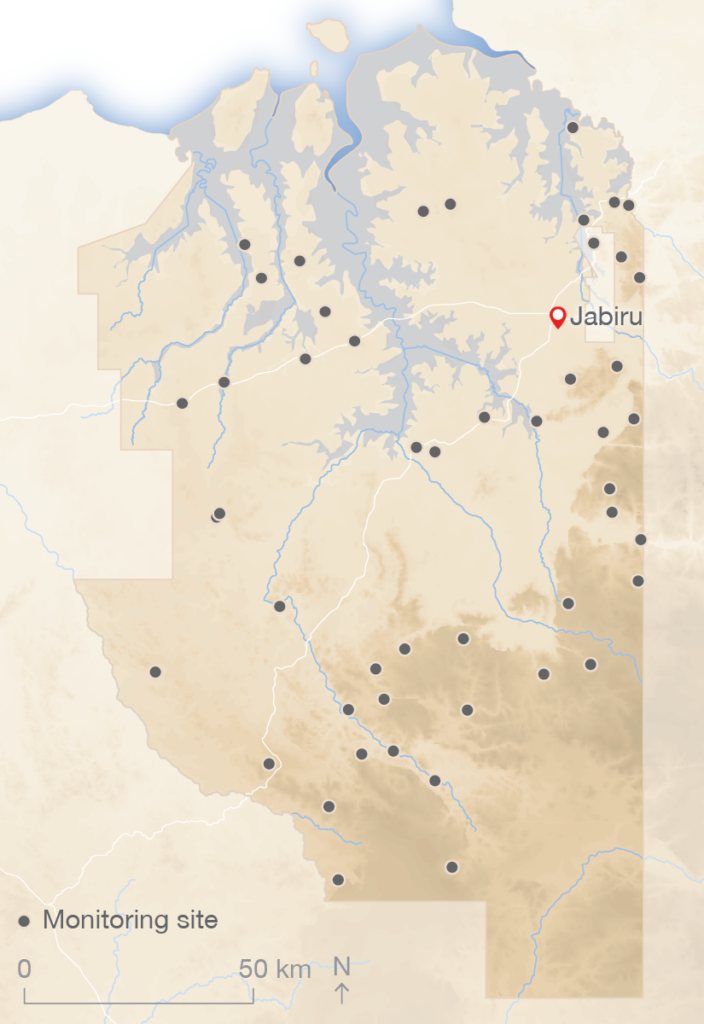

Locations of the 49 monitoring sites surveyed in Kakadu National Park.

The revised selection of sites was mostly drawn from the original larger pool of monitoring sites to maintain spatial continuity of monitoring. Final site selection was also undertaken in consultation with Traditional Owners and park managers.

We surveyed 49 of the 50 sites between April and August 2019 using our new sampling protocol. We collected information on 258 mammal, bird, reptile and amphibian species, including introduced animals such as buffalo and cats. Twelve threatened species were detected (5 mammals, 4 reptiles and 3 birds) – Arnhem rock-rat, black-footed tree-rat, fawn antechinus, northern quoll, pale field-rat, floodplain monitor, Mertens’ water monitor, Mitchell’s water monitor, yellow-snouted gecko, red goshawk, partridge pigeon and white-throated grasswren. The northern quoll, which almost disappeared from the NT with the arrival of cane toads, was found to be persisting in low numbers across the park.

The revised design has increased our ability to monitor a wider range of animal species. For example, the arrays of 5 camera traps are effective at detecting small mammals, large goannas, feral herbivores, feral cats and dingoes – these species were rarely detected with the previous monitoring design. For the first time, occurrences of feral cats, introduced herbivores and pigs were detected with enough sensitivity for effective monitoring. Threatened species such as the northern quoll and fawn antechinus were detected at some sites by camera trapping but not other methods. Funnel traps caught a variety of snakes and lizards that weren’t adequately detected by other methods, providing us with improved data for reptiles. These improvements in detectability, along with the increase in monitoring frequency, will improve the program’s ability to assess the current and future state of faunal communities within Kakadu and to track their trajectory of recovery or decline.

Not all fauna species are detected by this general ecological monitoring program. Many species that are rare or restricted to specific habitats need more targeted monitoring and specific sampling methods. This survey identified several threatened species, such as the white-throated grasswren, northern brush-tailed phascogale, floodplain monitor and Arnhem rock skink, that may be high priorities for additional targeted monitoring.

In addition to providing a valuable update on the long-term trends of fauna, we gained more robust information on habitat condition and threatening processes (e.g. occurrence of feral herbivores, feral cats, weeds and fire intensity). This information will enable better interpretation of patterns of change in species occurrence and faunal assemblages across the park that are attributable to these threatening processes.

The yellow-snouted gecko was one of several threatened species detected by the surveys. Photo Chris Jolly.